—

Documentation is an important part of professional practice. It is a means to disseminate singular works of art more widely and allows ephemeral works to have a life beyond the time of their creation and/or exhibition. Documentation can also be a tool for the artist to interrogate their work and processes, and to think more deeply about what they are doing over time. Documentation can help us to think about and discuss work without having to be in the same space as the original work.

In many cases there is a clear distinction between the work of art and the documentation. We can see this distinction in the way that works often have nuances that we can’t appreciate in a video or photograph while videos and photographs can show us something about process that we can’t see in the final works.

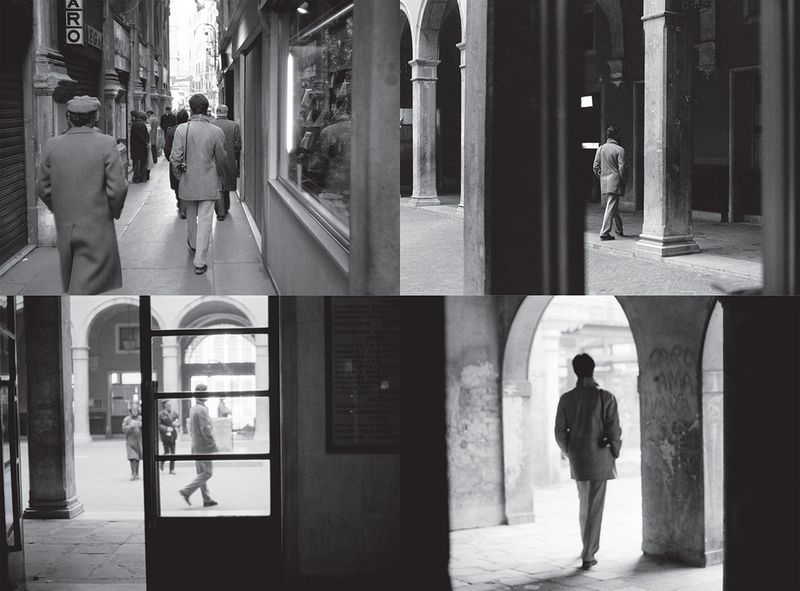

There are also ways of making work where there is little or no distinction between the documentation and the work. Suite Vénitienne by Sophie Calle is an example of this. We can also think of performance-video works in which the video can be both the documentation of an action and the work itself.

Sophie Calle

Sophie Calle documented the process of following strangers on the street with text and photographs. In this case the documentation is also the work.

Forms of Documentation

Documentation can be in any form that is appropriate to your subject. Consider how you can show visually the aspects of the work that you are trying to communicate through your documentation. This might involve using photos, video, audio, drawings, maps, a website, a folio of support drawings, or a folder of digital files. Written descriptions of works and/or processes are also an important form of documentation. You might think about how written descriptions can add extra information that you can’t communicate visually. For example you can use text to describe aspects of the work that do not come across in photographs. Documentation doesn’t always have to be visual. Sometimes text or audio might be the best form of documentation for a particular work or process. Use your imagination: your documentation can be in any form that is appropriate to your subject.

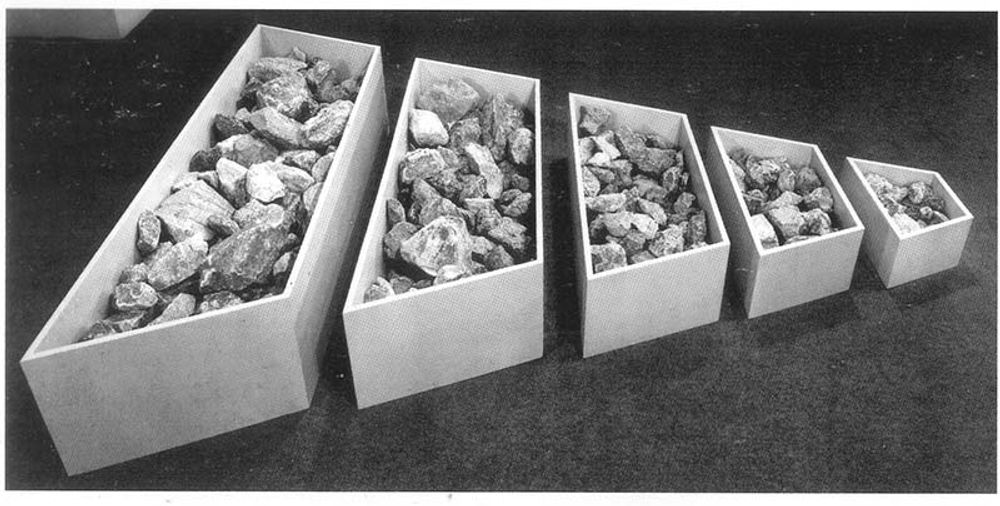

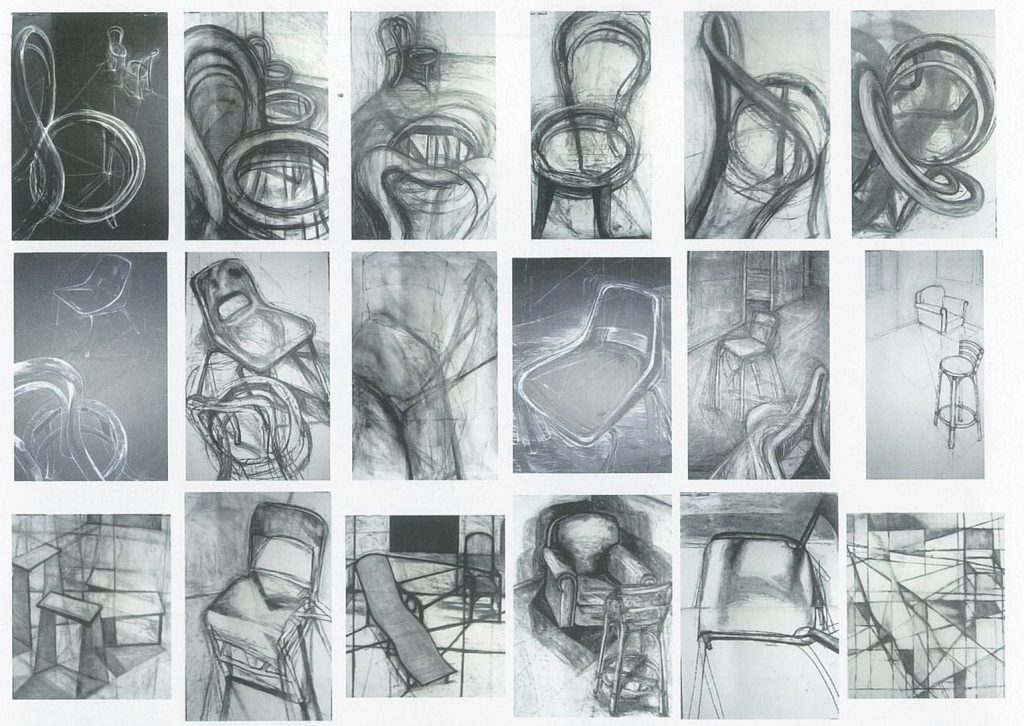

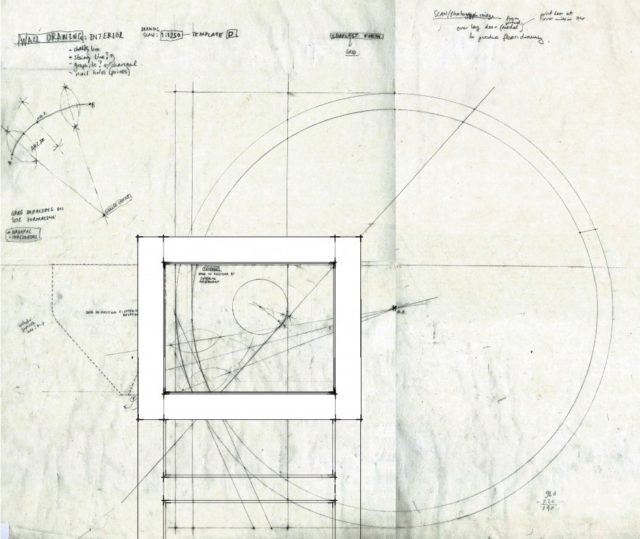

Elisabeth Vullings

Elisabeth Vullings used text, drawings, plans, objects and photographs to document a site.

Photographing or Videoing Your Work

Ideally choose a wall or area of your space that has bright, even, indirect lighting. Different angles and distances can help show more of your work. A wide shot that gives us a sense of the work in space and can also help us to understand scale and possible relationships between works. A closer shot that frames individual works as tightly as possible can help us to appreciate what is going on in individual works. Getting in really close to show significant details can help us to appreciate textures and materiality in a way that isn’t possible with wider shots.

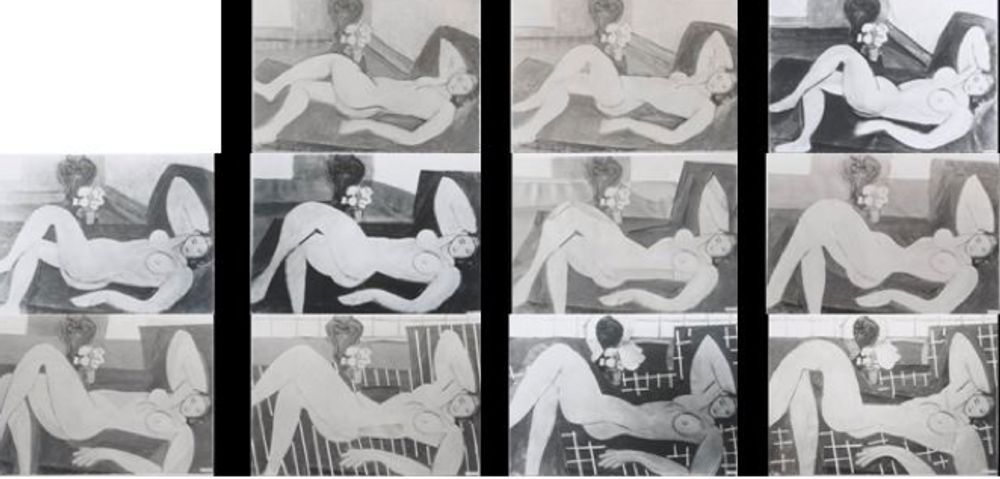

Henri Matisse

Matisse documented more than twenty states of a painting in progress with black and white photographs.

Organising Your Documentation

It is important to keep your documentation well organised. This helps to make your documentation accessible to others. One simple way to do this is to organise your material is by date. That way we can all see the progress that you make across the year.

Your photographs or other digital files can be organised on your computer or by printing them out. If you are generating a lot of files, keep a separate folder for each week’s work. If you are generating fewer files a folder for each month might suffice. Place all of your files for that week or month into the folder. You may need sub-folders for different types of documentation (one for images, another for sounds, a third for videos etc.).

We also encourage you to write a few sentences about each of the works that you create and document. Write down the date then reflect on any problems or issues you may have encountered in creating the work and what you learnt through the process.

If you are working with physical materials or printing out images, organising your material chronologically may still be a good way to go. Please discuss with your lecturer what the best forms of documentation might be for your particular project.